By JoAnn Alumbaugh, Featured in Farm Journal’s Pork

It’s time to move weaned pigs out of the farrowing house, and you notice significant differences in size and quality. Inconsistency can create problems in the nursery and finishing phase because variation will only increase as pigs grow. Efforts to improve uniformity and consistency before pigs are weaned will pay dividends in the long term.

As explained in the first and second articles on producing a quality weaned pig, the characteristics of a quality weaned pig – health, thriftiness, age and weight, and consistency – are influenced by genetics, management, health and nutrition.

Genetics

Genetics influence the number of pigs per litter. Still, without the added selection of birthweight, pre-wean survivability and the sow’s milk-ability, the number of potential quality weaned pigs can diminish.

Producers should use genetic lines proven to deliver matched quality and consistency in each litter and across weaning groups, says Juan Carlos Pinilla, DVM, Regional Technical Services Director for PIC.

“Production flow really matters,” he says. “Every group should be similar to the groups preceding and following in terms of age, weight and number. If the groups are different, you may be tempted to go to the room that will be weaned next to fill the nursery, but those pigs are at least 5 days younger. Their immunity is different and that could be a challenge.”

Younger pigs could look similar in weight, but their physiological development is different, and they could become a challenging subpopulation in the nursery, says Pinilla. Using multiple maternal lines may cause variation in piglet birth weight and daily growth. And when you add in numerous different boar lines, variation may be exacerbated.

“You could have five or six different genotypes born into the farm,” says Pinilla. “Genetic lines should be kept to a minimum if a producer wants to have consistent pigs,”

Parity management

Parity structure impacts efficiencies and consistencies of the piglet.

“The quality of the piglets at birth, and consequently at weaning, is partially driven by the age of the dam,” he says. “Litters born from P1 females tend to be born 10% to 13% lighter than other piglets. That is a challenge because there is a high correlation between birth weight and weaning weight.”

On the other end of the spectrum, birthweight variation within a litter is probable if too many older sows are farrowing.

“You might have 16 good piglets but one or two per litter may be smaller, and that forces farms to do more management. That’s why parity matters, related to younger and older females.,” explains Pinilla.

Jose Piva, PIC Technical Services Manager, agrees, noting the best sows for raising piglets are parities 2, 3 and 4.

“Sows at parities 8 to 10 are not the same as they were at a younger age in terms of milking ability and teat quality,” he says. “There is more variation in birth weight and small piglets are less competitive.

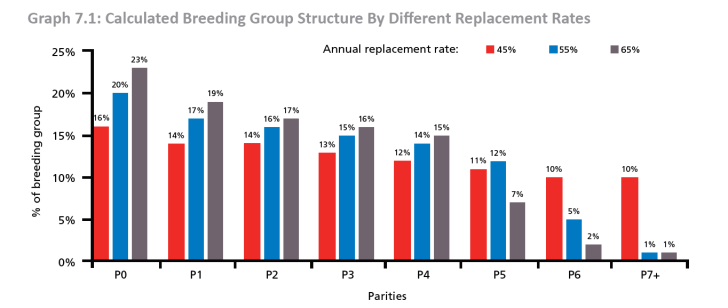

Execute parity management to avoid the extremes, with parities either too high or too low. Pinilla recommends a 50% to 55% replacement rate. Use culling as an opportunity to eliminate animals that are not producing to expectations or that can create future issues (i.e., lameness) and are not needed to maintain throughput.

Gilt management

Gilt pool quality is important for continuous improvement of the sow herd says Piva. Performance variation across systems and even within systems can partly be attributed to the quantity and quality of gilts at their first breeding.

It’s important to ensure enough grandparent (GP) animals are in the herd to guarantee the necessary flow of quality gilts. A general rule to safely meet this need is having 8% to 10% of total sow inventory be GP females. Plan multiplication size and gilt-production targets to have the right elite genetics for parity distribution.

“We know farms have to close sometimes for health reasons without gilt introductions,” explains Piva. “We need a continual flow of gilts, but if we’re forced to do something different, it’s important to have additional gilts for the next 5 or 6 months so we can cull the older animals as needed.”

“In simple terms, gilts allow a farm to hit its breeding targets,” Pinilla says. “However, if the gilt flow is not producing enough quality pigs, the producer has to change the parity flow. It’s better to have a sow that farrows seven piglets than to have an empty farrowing crate.”

Farrowing house management

Sows need the right environment in which to farrow as well. Piglets need the right environment to thrive.

“If it’s too cold or too hot in the farrowing room, we can affect piglet quality,” says Piva. “If the pig is chilled after birth and doesn’t get enough colostrum, it is harder for it to maximize its potential. Sow body condition, access to food and water, the environment of the sow, and colostrum intake are critical.”

Piva recommends placing like-parities together so they can be properly managed. For example, parity 1 and 2 sows require similar management and placing them near each other makes management easier and more efficient for staff.

Inducing should be minimized or at least carefully considered, Piva and Pinilla point out.

“When we induce a high percentage of sows, we can get piglets that are not prepared to survive and thrive,” says Piva.

“Weaning weight is associated with birth weight. When too many sows are induced, chances are some of those gestations will be terminated a few days too early.,” says Pinilla. “Those piglets could be born challenged – not only because they’re lighter but also due to compromised pulmonary function. We believe induction is a tool but should be used only when it’s needed.”

Nutrition

“Proper nutrition is a big part of piglet quality,” says Piva. “And piglet quality depends in large part on the way we feed the sows in gestation. We can create problems if we feed too much or not enough, though I see more damage with sows being overfed in terms of piglet quality. It’s difficult to produce a good quality piglet when sows are not in good body condition.”

Perform body condition assessments at weaning, 30 days, 60 days, and 90 days of gestation. Adjust feeder settings when body condition assessments are performed so sows enter the farrowing room in optimal condition. Piva recommends producers target having 90% of females entering the farrowing room in ideal condition.

Continuous improvement

As genetics and management have improved, Piva believes sows are much more prepared to raise 14 to 18 piglets than they were 10 years ago.

“A good proportion of sows should have 15 to 17 piglets,” he says. “With the right genetics, the right environment, the right feeding and the right management, I believe 55% to 60% of the sows in a herd should be able to wean more than 14 piglets. Sows are milking better and producing a more robust piglet.”

That continuous improvement bodes well for the future, as producers incorporate the needed tools and protocols to produce more quality weaned pigs.